Text by Bob Hankinson, Photo's by Dan McKenzie

Servicemen were working at Llanberis through much of the Cold War, clearing the Weapons that were abandoned there. Our visit was on

a warm sunny day in July. The obvious part of the site resembles eight

parallel railway tunnels opening out into a vast concrete tank about 100 metres

by 60, with walls 12 metres high. The area was a cut-and-cover construction,

formed in the bed of a large slate quarry. There were two levels, and the site

was very compact, albeit large. A similar construction was used at Harpur Hill -

but never again.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Click on the on picture for a larger view

The ceiling of the lower levels forms the floor of the upper levels, which have an arched roof, covered with 8 metres depth of slate waste. One of the galleries is wider and slightly higher than the others, and has a single track railway line running into it the full length, with a wide platform on the North West side and a narrow one the other. An entire train of railway wagons could be brought in for loading and unloading. Such a train, of 27 wagons according to McCamley, was inside of 25 January 1942 when the roof of half the space collapsed, burying the wagons and blocking the only goods exits but not exploding. At the time, 14,000 tons of munitions were stored there, all suddenly inaccessible. Over the next nine months most of the bombs were recovered through the back entrance, which was an adit to another slate quarry. This was a seventy-foot deep pit, and the bombs had to be lifted out of the pit. An inspection at Harpur Hill showed signs of weakness, and much of the overburden was hastily removed. Since the level of the overburden at Llanberis today is not level with the top of the quarry pit, this may also have been done at Llanberis over the uncollapsed part.

Inside, the remaining galleries are

very dry, clean and in good condition, with limited graffiti and no vandalism

and not much litter. The walls in the covered part are all painted white, and

there is evidence that this is original paint from 1941 (since none of the

brickwork is painted). The lower level is about 15 feet from floor to ceiling,

with walls running the full length separating the galleries. Each gallery is

about 24 feet wide and over two hundred feet long, ending in a thick brick wall,

which was built to separate the uncollapsed part from the area where the

collapse occurred. The wider gallery is between gallery B and gallery C, and is

not itself lettered. Except in this wider gallery with the railway line,

concrete pillars about 12 feet apart run down the centre, supporting a concrete

beam running the length of each gallery. These help to support the ceiling,

which forms the floor of the level above. They are apparently original, because

each corner has a steel rubbing piece built in, as do the other openings but not

the brick reinforcements seen in some places, which I believe to have been

installed as strengthening after the collapse. The sidewalls have square

openings about 15 feet wide every so often, some of them bricked up. The

galleries are lettered A to H on the lower level and J to S on the upper level.

Each gallery was numbered into eleven bays. The bay numbers can be clearly seen

on the walls, but there is no divider between the bays except a red roundel

painted high on the wall midway between the numbers. The numbers run from 6 to

11 on upper and lower levels, leaving bays 1 to 5 in the open area where the

collapse occurred. Roughly half of the total underground area is thus now open

to the air (the "tank") and half still covered.

There are two galleries to the right of the railway line, A and B downstairs and

J and K upstairs. The furthest right is J gallery upstairs. A / J is much

shorter than the other galleries. It has only bays labelled J8, 9 and 10. At the

back, part of the floor is higher, and this is a blind gallery, running forward

only as far as J8. The others all run from 11 to 6 before ending in the brick

wall, but for gallery J there is no brick wall and no external sign at all. J10

is also not full width. My guess is that the original quarry was slightly wider

here, and the builders took advantage of the extra space.

Gallery M has two lifts. One is at C6 / M6, hard up against the brick wall and

barely any use. Surprisingly, no effort appears to have been made to open the

other side of the lift so that it could have been used more readily. The other

lift is at C9 / M9. The wiring is very old, gutta percha insulation and no sign

of post-war modernisation.

The upper level galleries are the same width as the lower, but they have an

arched roof and there is no line of central pillars as in the lower galleries.

The doorways between the galleries are smaller than below, and arched rather

than square. Several have been reinforced after the original build with 4

courses of brick, also formed into a beautiful arch, but without the steel

corners seen on the original concrete construction. This brickwork narrows the

opening from 12 foot to six foot wide, and drops the height of the arch from 11

to 7 foot. Around M, N and P several of the archways are completely

bricked up. There is a single staircase between lower and upper levels, at C11.

There are some few electrical fittings left. Main power came in through the back

tunnel. Most of galleries show signs of tubular conduit for hanging lights, and

a few of the reflectors remain. All of the switches have gone, except the casing

of one which shows clearly that it was of the type used in furls and explosives

stores, which contains the spark inside the housing.

Two bits of official graffiti have been painted on neatly, and again are likely

to date from 1942. They say that the practice of spitting is disgusting and must

cease. Anyone caught spitting will be dismissed. This points to a mainly

civilian workforce, since dismissal is not the term that would be used for a

serviceman facing a charge.

There are three tunnels leading to the main storage space. Two open into the

"tank" - the open part where the collapsed concrete, bombs and slate

backfill have been removed. The main access tunnel is about 15 feet wide, square

section part of the way and is arched the rest. It is quite short, has a bend

and is large enough for a railway wagon. It ends now at a palisade fence and

gate. It has been shotcreted, and this could have been done at the same time as

the work on Dinorwig power station (which has extensive shotcreting) or may be

much more recent, according to one

eyewitness account. .

The second tunnel is smaller and is now a dead end, and is not shotcreted. You

can enter from the storage area, but after a bend to the right the tunnel is

blocked to the ceiling with a jumble of waste stone. After the bend the tunnel

is concrete lined and arched, with signs of decay in the concrete. Reinforcing

rods could be seen, about 3cm thick and 12 cm apart.

The third tunnel is at the back of the storage area in gallery

D, and is mostly unfinished rock. It is about 7 feet high. The floor is very

rough concrete, but there are rotten wooden sleepers set into the concrete. An

open water channel runs on one side, with water running into the workings to the

start of the tunnel, where it drops into an inspection pit and is carried away

in a large earthenware pipe about a foot in diameter. It is the noise of this

falling water that you hear throughout the upper galleries, sounding at first as

if fans were running. At the bend of the tunnel, the straight passage is bricked

off, while the open tunnel bends to the left and goes into the open air past a

vertical shaft up which power cables ran. My guess is that this was an old adit,

adapted for power supply and emergency exit and then adapted again for the

painstaking removal of the munitions after the collapse. Significantly, the

floor of this tunnel is not level with the floor of the storage galleries, being

about a foot higher. This would have added to the handling problems getting the

munitions out in the recovery operation.

The back pit is about seventy feet deep, and maybe 100 feet square. Off to the

right is another adit, leading slightly downwards and filled with water, with no

sign of an exit.

Back outside in the "tank", there is little to see. The space between

the railway platforms has been filled recently with rubble, and floor was clear

but has had several loads of spoil tipped there. Our guide had said that on his

last visit the floor was completely clear, no stone larger than a fist anywhere.

On the walls are the remains of wooden signboards every few feet, which would

have been bay labels (unlike the ones inside, which are painted). This lends

support to Nick McCamley's comment that the cleared open area was used

from 1943 for storage of incendiaries.

After the war there was long term activity at Llanberis, in the form of a small

RAF detachment of bomb disposal people, patiently clearing dumped weapons. The

story goes that large quantities of incendiaries were dumped at the end of the

war into the water filled pit to one side of the main storage area. Once the

existence of this hoard became known, it all had to be cleared.

Text Bob Hankinson 2000 ©

The following text and picture about Llanberis was taken from the book

"Designed to Kill" by Major Arthur Hogben, ISBN 0850598656

Probably the largest land clearance task in respect of the weight of ordnance recovered was that at Llanberis. Royal Air Force Llanberis was opened as an explosive storage unit in May 1941, close to the Snowdonian village of that name in north Wales. The site occupied a large complex of disused slate quarries and interlinking tunnels. Between 1941 and July 1956 when the unit closed it had been used as a bomb store, a demolition area and a burning pit.

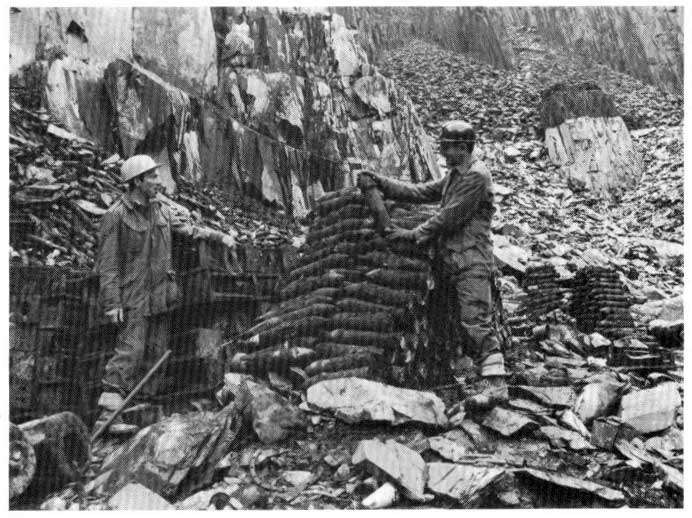

The demolition and burning of explosives within the quarry area started in June 1943 when the Royal Air Force School of Explosives moved to the site. The school curriculum included the destruction of explosives, so large quantities of bombs and pyrotechnics were brought in for demolition or burning. The destruction of explosives continued until July 1956 when the unit was closed. Included in the destruction programmes were virtually every type of explosive item on the Royal Air Force wartime inventory. Unfortunately, as sometimes happens with mass demolition, a proportion of the items were not completely destroyed. Thus this large and practically inaccessible complex of quarries was known to contain quantities of explosive items. As such the site solicited a certain amount of indiscriminate dumping of unwanted or recently recovered explosive items. The shape of the site was such that much of the explosive material dumped ended up on ledges and slate outcrops, never reaching the quarry bottoms. More still had been dumped or fallen into the lakes, which had formed in the quarries during the years of inactivity between 1956 and 1969.

It was in this latter year, 1969 that the decision was taken to clear the entire site of explosives and explosive debris. The task was given to 71 Maintenance Unit EOD Flight from Royal Air Force Bicester (later to be designated No 2 EOD Unit, RAF). By the time the task was completed in Octoberl975,the personnel of the Flight had become expert in lifting tons of explosives from the quarry pits and lakes and in the handling of special mechanical equipment. They had also learnt the arts of tunneling and rock climbing, which in the earlier days had been the only ways of gaining access to some of the pits and their surrounding ledges. This must have been one of the few bomb disposal tasks carried out by any Service where members of the unit had first to be instructed by a Mountain Rescue Team. The various rock climbing techniques and rescue procedures taught were essential to enable members of the unit to reach much of the explosive ordnance with which they had to deal.

From 1969 onwards, the various pits and tunnels were progressively cleared. Members of the EOD Flight burrowed further and deeper into the debris and slate rubble to uncover such items as incendiary bombs and high explosive bomb detonators. The latter, together with the numerous bomb fuses, which were uncovered, were in an extremely hazardous condition and required careful handling. With the help of the Royal Engineers, roads were constructed into the more difficult pits and the' fly on the wall' approach became less frequent. However, at no time throughout the six years of the project was the task rated any easier than' very difficult '. It was not a question of true grit and stamina, but rather an excess of slate, grit and slime.

Royal Navy divers were co-opted to investigate the contents of a large lake in one of the pits as it was suspected that it might contain some explosive items. The divers reported that the bed of the lake was littered with explosive items including a number of large bombs. Subsequently, over 20,000,000 gallons (90,920,000 liters) of water and sludge were pumped out. By April 1973 the lake was emptied revealing everyone's worst fears—it took a further two years of hard labour to recover and dispose of the explosive items revealed. Fortunately, this pit was one of those to which 38 Engineer Regiment, RE, had constructed a road, otherwise the task would have been impossible.

On completion of the task, 71Maintenance Unit EOD Flight had moved approximately 85,000 tons (83,364 tonnes) of slate and debris, recovered and disposed of 352 tons (357 tonnes) of explosive items together with 1,420tons (1,443 tonnes) of non-explosive ordnance debris. Many people were involved in this task, too numerous to quote by name, but a few who played a prominent part deserve to be mentioned. Those directly involved at the work face were Flight Lieutenants E. S. T. Tout, W. Jones and J. Thomson, RAF, all of whom successively commanded the EOD Flight concerned. In the early day s of the task the workforce consisted of an eight-man team headed by Flight Sergeant Russell, RAF, who was awarded the Medal of the Order of the British Empire (BEM) for his work during the initial opening up of this extremely hazardous operation. Other senior non-commissioned officers involved at some stage or other in the project were Flight Sergeant G. Twine, Flight Sergeant E. K. Tumman, BEM (who moved to Llanberis direct from the Maplin Sands task), Chief Technician D. Andrews, BEM, and Sergeant B. Rutter (who was later killed whilst clearing British cluster munitions following a trial drop).